In early January 2026, Israeli authorities formally notified Palestinian communities, including the Municipality of al-Ezariyeh and residents of Bedouin communities in Jabal al-Baba and Wadi al-Jamal, of their intent to begin construction of a major bypass road linking El-Ezariyeh and A-Zae’im within 45 days. This road, widely referred to as the “Sovereignty Road,” is designed to create a separate transit corridor for Palestinian vehicles while reserving existing main roads for Israeli traffic. As such, the Palestinian communities in and around the “E-1” corridor are facing an imminent escalation in settlement-related infrastructure that threatens to deepen territorial fragmentation and restrict movement across the occupied West Bank.

The Israeli government has labeled the route a “security road,” a designation that bypasses the formal planning process. Under this classification, the planned road will not undergo review by the higher planning council, effectively removing Palestinian access to the preexisting roads that connect the southern part of the West Bank with the northern parts of the West Bank.

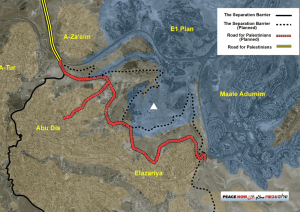

(Source: Peace Now, 2026; the white triangle indicates Jabal al-Baba, added by BIHR)

(Source: Peace Now, 2026; the white triangle indicates Jabal al-Baba, added by BIHR)

The bypass road will expand the current dual-road system, diverting Palestinian traffic onto a separate path and opening up the broader Ma’ale Adumim settlement and “E-1” area to exclusive Israeli use. The planned construction will run over privately owned land and several residential sites, with demolition orders threatened for structures in its direct path.

Sources from Al-Ezariyeh municipality confirm that approximately 3,000 dunums of land have already been confiscated through military seizure orders for the purpose of constructing this route and associated settlement infrastructure. Local municipal sources also highlight several immediate concerns linked to the road and the broader “E-1” project:

- Isolation of Communities: The new bypass road would isolate towns such as El-Ezariyeh, Abu Dis, and Sawahra from surrounding Palestinian areas, limiting access to essential services and economic opportunities.

- Displacement Threats: Demolition orders to residents in the bypass corridor would result in their forced displacement and violate a wide-set of their fundamental rights.

- Fragmentation of the West Bank: Combined with existing closures and checkpoints, the new bypass road contributes to a broader pattern of territorial fragmentation that restricts north–south Palestinian movement and undermines community cohesion.

Alongside the road announcement, expansion of the “E-1” settlement plan, including the approval of thousands of new housing units, has moved forward under the current Israeli government. These projects, which have temporarily stalled due to international pressure and diplomatic interventions, are now progressing as part of a broader infrastructure build-out in the concept of “Greater Jerusalem”, linking the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim to Jerusalem with an all-Israeli road.

Legal Framework and Analysis

The West Bank, including the E1 corridor and the areas surrounding Ma’ale Adumim, constitutes occupied territory under international humanitarian law. As such, Israel is bound by the rules of occupation as codified in the 1907 Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, as well as relevant norms of customary international law. International human rights treaties to which Israel is a party, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), also apply extraterritorially to the occupied Palestinian territory, as affirmed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and UN treaty bodies.

The construction of settlement-related infrastructure in the E1 area, including the announced “Sovereignty Road,” must be assessed within the long-established prohibition on the transfer of the occupying power’s civilian population into occupied territory under Article 49(6) of the Fourth Geneva Convention. While Israel frequently characterizes roads and infrastructure as “security” or “transportation” measures, international law evaluates such actions based on their purpose and effect, not their formal designation.

The planned bypass road is explicitly designed to facilitate the illegal Israeli settlement continuity between Jerusalem and Ma’ale Adumim, while segregating Palestinian movement into a separate, inferior transportation network. This functionally supports settlement permanence and territorial integration, amounting to a de facto annexation measure, prohibited under international law. The ICJ, in its Advisory opinion on the legal consequences of the policies and practices of Israel in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem (19 July 2024), affirmed that measures altering the demographic composition or permanent character of occupied territory violate the law of occupation, irrespective of whether formal annexation is declared. In this opinion, the court highlighted that settlement expansion, land confiscations, and other practices that create a de facto permanent presence constitute breaches of the rules governing occupation. In light of this, the ICJ concluded that Israel’s presence in the oPt is unlawful.

Orders and the threat of displacement affecting Palestinian communities in the road’s path engage the prohibition on forcible transfer under Article 49(1) of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Even where displacement occurs without direct physical force, international law recognizes that a coercive environment, created through land confiscation, movement restrictions, and denial of services, can amount to unlawful forcible transfer.

The cumulative policies associated with the E1 plan and the “Sovereignty Road” contribute to such a coercive environment, particularly for Bedouin communities, whose vulnerability has been repeatedly recognized by UN bodies and humanitarian actors.

The E1 project and associated infrastructure further fragment the territorial contiguity of the West Bank, severing north–south Palestinian movement and isolating East Jerusalem from its Palestinian hinterland. This undermines the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination, a peremptory norm of international law affirmed in the UN Charter and common Article 1 of the ICCPR and ICESCR.

The ICJ has held that measures which permanently alter the geography and viability of a future Palestinian state violate this right. The consolidation of Israeli control over the E1 corridor, therefore, carries legal consequences beyond individual violations, implicating broader international obligations not to recognize or assist unlawful situations.

Under the law of state responsibility, Israel bears responsibility for internationally wrongful acts arising from settlement expansion, land confiscation, and discriminatory movement regimes. In addition, third states have an obligation not to recognize as lawful situations created by serious breaches of peremptory norms, nor to render aid or assistance in maintaining such situations.

The advancement of the “Sovereignty Road” and the acceleration of the E1 plan thus engage not only Israel’s obligations as an occupying power, but also the responsibilities of the international community to ensure respect for international law. The reported confiscation of approximately 3,000 dunums of land through military seizure orders raises serious concerns under Article 46 of the Hague Regulations, which protects private property from confiscation, and Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits destruction of property unless rendered necessary by military operations.

The designation of the road as a “security road,” thereby bypassing standard planning procedures and judicial scrutiny, does not satisfy the stringent threshold of military necessity required under international humanitarian law. Infrastructure designed primarily to benefit settlers and restructure movement patterns cannot be justified as a temporary or necessary military measure. Where demolitions or displacement result, such actions may constitute grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The creation of a dual-road system that reserves primary roads for Israeli use while diverting Palestinians to separate routes engages Israel’s obligations under Article 12 of the ICCPR, which guarantees freedom of movement. The cumulative effect of checkpoints, gates, and segregated infrastructure imposes disproportionate and discriminatory restrictions on Palestinians’ ability to access healthcare, education, livelihoods, and family life.

Such policies must meet the tests of legality, necessity, and proportionality. Given the structural and permanent nature of the restrictions and their clear linkage to settlement expansion rather than immediate “security” threats, these measures fail to meet international human rights standards and contribute to a regime of systematic segregation.